-

Prolog vs. Lisp: Explorando a Programação Lógica e Funcional

A escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença no desenvolvimento de aplicativos complexos e sistemas inteligentes. Neste post, vamos mergulhar na comparação entre duas abo...

-

Haskell vs. OCaml: Escolhendo a Linguagem Funcional Ideal para o seu Projeto

Na era da computação moderna, onde a eficiência e a confiabilidade são cruciais, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença. Neste artigo, vamos explorar as característ...

-

Dylan vs. Smalltalk: Programação Dinâmica e Orientada a Objetos

Quando se trata de linguagens de programação, a diversidade é abundante, cada uma com suas próprias características, forças e aplicações específicas. Neste blog, vamos mergulhar na comparação entre...

-

JRuby vs. Groovy: Desenvolvimento JVM Dinâmico

A escolha entre JRuby e Groovy pode ser um desafio para desenvolvedores que trabalham em ambientes Java. Ambas as linguagens oferecem vantagens únicas, mas é importante entender as diferenças para ...

-

V vs. Zig: Linguagem Certa para Desenvolvimento de Sistemas e Segurança

Na era digital em constante evolução, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa se torna cada vez mais crucial para o desenvolvimento de sistemas eficientes e seguros. Neste artigo, vamos explora...

-

Crystal vs. Nim: Desenvolvimento de Sistemas e Performance

O mundo do desenvolvimento de software está em constante evolução, e as linguagens de programação desempenham um papel fundamental nesse cenário. Duas linguagens que têm ganhado destaque são o Crys...

-

Tcl vs. Expect: Explorando as diferenças na Automação de Tarefas

A evolução da tecnologia trouxe consigo uma série de ferramentas e linguagens de programação que visam facilitar a automatização de tarefas. Neste cenário, duas opções se destacam: Tcl (Tool Comman...

-

Idris vs. Agda: Explorando a Programação Funcional e a Tipagem Dependente

No mundo em constante evolução da tecnologia, a busca por linguagens de programação cada vez mais poderosas e seguras é uma prioridade. Neste cenário, duas linguagens se destacam: Idris e Agda. Amb...

-

Jai vs. Odin: Linguagem Certa para Desenvolvimento de Sistemas de Alto Desempenho

Quando se trata de desenvolvimento de sistemas e aplicações de alto desempenho, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença. Neste post, vamos explorar duas opções promi...

-

Jai vs. V: Qual a melhor linguagem para desenvolvimento de sistemas de alto desempenho?

A escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer uma grande diferença no desempenho e eficiência de um sistema. Neste post, vamos comparar duas linguagens emergentes, Jai e V, que estão se de...

-

Pony vs. Ponylang: Concorrência e o Desenvolvimento de Sistemas

A indústria de tecnologia está em constante evolução, e as linguagens de programação desempenham um papel fundamental nesse cenário. Duas linguagens que têm chamado a atenção são o Pony e o Ponylan...

-

Q# vs. Qiskit: Diferenças no Desenvolvimento de Computação Quântica

A computação quântica tem sido um campo em rápida evolução, com diversas linguagens e frameworks surgindo para permitir que desenvolvedores explorem esse novo paradigma computacional. Neste post, v...

-

TypeScript vs. Dart: Quam melhor para Desenvolvimento de Aplicativos Web e Móveis?

A escolha entre TypeScript e Dart é uma decisão importante para qualquer desenvolvedor que esteja construindo aplicativos web e móveis. Ambas as linguagens oferecem recursos poderosos e têm suas pr...

-

Q# vs. Qiskit: Diferenças no Desenvolvimento de Computação Quântica

A computação quântica tem sido um campo em rápida evolução, com diversas linguagens e frameworks surgindo para atender às necessidades dos desenvolvedores. Neste artigo, vamos explorar duas das pri...

-

AutoIt vs. AutoHotkey: Ferramentas Poderosas para Automação de Tarefas no Windows

Neste mundo digital em constante evolução, a necessidade de automatizar tarefas rotineiras e aumentar a produtividade é cada vez mais evidente. Duas ferramentas que se destacam nesse cenário são o ...

-

C++20 vs. Rust: Desenvolvimento de Sistemas e Segurança

A evolução das linguagens de programação é um tópico fascinante, especialmente quando se trata de comparar duas abordagens tão distintas como C++20 e Rust. Ambas as linguagens desempenham papéis cr...

-

Haxe vs. CoffeeScript: Melhor Opção para Desenvolvimento Multiplataforma

Na era digital em constante evolução, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença no sucesso de um projeto. Duas opções que têm se destacado no cenário do desenvolviment...

-

Lua vs. JavaScript: Linguagens para Desenvolvimento de Jogos e Scripts

Quando se trata de desenvolvimento de jogos e scripts, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença. Duas opções populares neste cenário são Lua e JavaScript, cada uma co...

-

Haxe vs. Dart: Escolhendo a melhor opção para Desenvolvimento Multiplataforma

Quando se trata de desenvolvimento multiplataforma, duas linguagens de programação se destacam: Haxe e Dart. Ambas oferecem soluções poderosas para criar aplicativos que funcionam em diferentes pla...

-

Vala vs. C#: Linguagem para Desenvolvimento de Aplicativos Linux e Windows

Ao escolher uma linguagem de programação para o desenvolvimento de aplicativos, é importante considerar as características e os recursos oferecidos por cada uma. Neste artigo, vamos comparar duas l...

-

Groovy vs. Java: Desenvolvimento de Aplicativos Dinâmicos

Quando se trata de desenvolvimento de aplicativos, os programadores têm uma variedade de opções à sua disposição. Duas linguagens de programação que têm se destacado nesse cenário são o Groovy e o ...

-

F# vs. Scala: Programação Funcional e Orientada a Objetos

A escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer uma grande diferença no sucesso de um projeto. Neste artigo, vamos explorar as características e aplicações de duas linguagens populares: F# e...

-

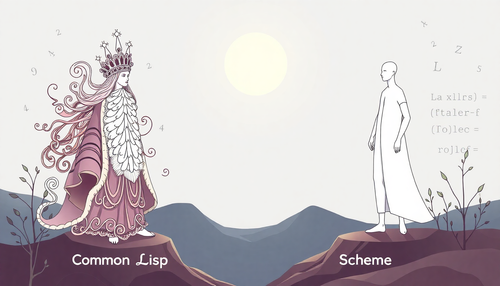

Common Lisp vs. Scheme: Explorando a Programação Funcional Acadêmica

A programação funcional tem sido um campo fascinante na ciência da computação, com linguagens como Common Lisp e Scheme desempenhando papéis importantes no desenvolvimento dessa paradigma. Neste ar...

-

Groovy vs. JRuby: Escolhendo a Linguagem Dinâmica Ideal para o seu Projeto JVM

A escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer uma grande diferença no sucesso de um projeto de software. Quando se trata de desenvolvimento JVM (Java Virtual Machine), duas opções dinâmica...

-

Smalltalk vs. Ruby: Qual a Melhor Linguagem de Programação Orientada a Objetos?

Quando se trata de desenvolvimento de software, a escolha da linguagem de programação é fundamental. Duas opções que têm se destacado no cenário do desenvolvimento orientado a objetos são o Smallta...

-

Dylan vs. Common Lisp: Explorando a Programação Dinâmica e Funcional

A escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença no desenvolvimento de sistemas complexos. Neste artigo, vamos explorar duas opções poderosas: Dylan e Common Lisp. Ambas ofer...

-

Pascal vs. Delphi: Linguagem para Desenvolvimento de Aplicativos Desktop

Na era digital em constante evolução, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença no desenvolvimento de aplicativos desktop. Duas opções que têm se destacado nesse cenár...

-

OCaml vs. F#: Comparando Linguagens Funcionais e de Tipagem Estática

Na era da computação moderna, onde a eficiência e a confiabilidade são cruciais, as linguagens de programação funcionais e de tipagem estática têm se destacado como opções poderosas. Neste artigo, ...

-

TypeScript vs. JavaScript: Tipagem Estática e Escalabilidade

Em 2025, a adoção de TypeScript deve aumentar em projetos de grande escala. Como uma superset do JavaScript, o TypeScript adiciona recursos de tipagem estática, melhorando a segurança e escalabilid...

-

Go vs. Python: Concorrência e Simplicidade

Em 2025, a escolha entre Go e Python para desenvolvimento de back-end e sistemas distribuídos se torna cada vez mais relevante. Ambas as linguagens possuem características únicas que as tornam atra...

-

Go vs. Java: Concorrência e Escalabilidade

Go (ou Golang) e Java são duas linguagens amplamente utilizadas para o desenvolvimento de aplicações robustas e de alta performance. No entanto, quando o assunto é concorrência e escalabilidade, ca...

-

Rust vs. C++: Segurança vs. Performance

Em 2025, a escolha entre Rust e C++ continua sendo um tópico de grande debate entre desenvolvedores de software. Ambas as linguagens são conhecidas por sua ênfase na performance, mas Rust se destac...

-

Kotlin vs. Java: Desenvolvimento Android Moderno em 2025

Em 2025, o desenvolvimento de aplicativos Android continua a evoluir rapidamente, com a linguagem Kotlin consolidando sua posição como a escolha preferida dos desenvolvedores. Desde que a Google a ...

-

Julia vs. Python: Velocidade e Análise de Dados

Em 2025, a linguagem de programação Julia está ganhando cada vez mais atenção no mundo da análise de dados e ciência de dados. Embora Python ainda seja a linguagem dominante nessas áreas, Julia vem...

-

COBOL vs. Visual Basic: Legado e Desenvolvimento Rápido

Nos dias atuais, as empresas enfrentam um desafio constante de equilibrar a necessidade de manter sistemas legados robustos e a demanda por soluções de desenvolvimento rápido e inovadoras. Neste ce...

-

C# vs. F#: Linguagem Certa para o seu Projeto

Como desenvolvedores, enfrentamos constantemente o desafio de escolher a linguagem de programação mais adequada para nossos projetos. Neste artigo, vamos explorar as diferenças entre C# e F#, duas ...

-

Kotlin vs. Swift: Qual a Melhor Opção para Desenvolvimento Móvel?

O desenvolvimento móvel é um campo em constante evolução, com duas linguagens de programação dominantes: Kotlin e Swift. Ambas têm suas próprias forças e fraquezas, e a escolha entre elas pode ter ...

-

MATLAB vs. R: Qual a melhor ferramenta para análise de dados e simulações?

A escolha entre MATLAB e R é uma decisão importante para profissionais que trabalham com análise de dados, modelagem e simulações. Ambas as ferramentas possuem pontos fortes e fracos, e a seleção d...

-

Elixir vs. Java: Concorrência e Desenvolvimento de Aplicativos

A escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer uma grande diferença no desenvolvimento de aplicativos, especialmente quando se trata de concorrência e escalabilidade. Neste artigo, vamos co...

-

Clojure vs. Kotlin: Linguagem para seu Desenvolvimento JVM e Concorrência

Na era da computação moderna, onde a complexidade dos sistemas e a necessidade de escalabilidade são cada vez mais desafiadoras, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a difere...

-

Bash vs. Perl: Linguagens de Scripting e Processamento de Texto

Em um mundo cada vez mais automatizado, a escolha da linguagem de script certa pode fazer toda a diferença na eficiência e produtividade de suas tarefas. Neste artigo, vamos explorar as característ...

-

Python vs. Perl: Análise de Dados e Scripting

A escolha entre Python e Perl é uma decisão importante para muitos profissionais que trabalham com análise de dados e automação de tarefas. Ambas as linguagens têm seus pontos fortes e aplicações e...

-

Haskell vs. Scala: Programação Funcional e Tipagem Estática

Na era da computação moderna, onde a eficiência e a escalabilidade são cruciais, a escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer toda a diferença. Duas opções que se destacam nesse cenário s...

-

Assembly vs. C: Baixo Nível e Performance

A escolha entre Assembly e C é uma decisão importante para desenvolvedores que precisam lidar com requisitos de alto desempenho e controle de baixo nível. Ambas as linguagens oferecem vantagens e d...

-

Scratch vs. Python: Qual a Melhor Linguagem de Programação para Iniciantes?

Quando se trata de aprender a programar, existem diversas opções de linguagens disponíveis, cada uma com suas próprias características e aplicações. Duas das linguagens mais populares para iniciant...

-

PHP vs. Ruby: Qual a Melhor Opção para Desenvolvimento Web Dinâmico?

Quando se trata de desenvolvimento web dinâmico, duas linguagens de programação se destacam: PHP e Ruby. Ambas têm suas próprias forças e fraquezas, e a escolha entre elas pode fazer uma grande dif...

-

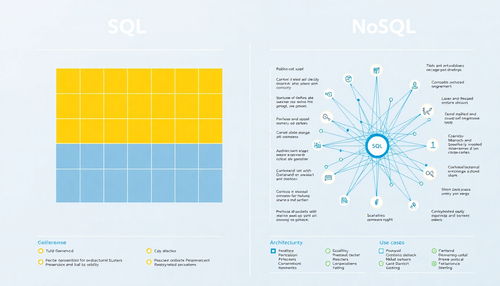

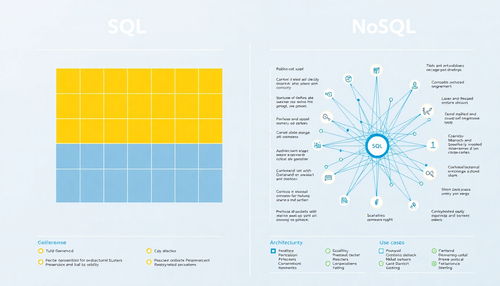

SQL vs. NoSQL: Solução de Gerenciamento de Dados para sua Empresa

Na era digital em que vivemos, a gestão eficiente de dados tornou-se fundamental para o sucesso de qualquer negócio. Empresas de todos os tamanhos e setores enfrentam o desafio de armazenar, proces...

-

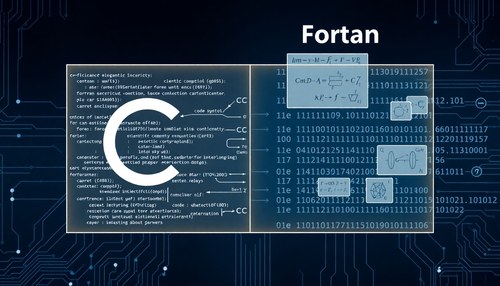

C vs. Fortran: Desempenho e Simulações Científicas

A escolha da linguagem de programação certa pode fazer uma grande diferença no desempenho e eficiência de aplicações científicas e de engenharia. Duas opções populares neste contexto são C e Fortra...

-

Integração da Inteligência Artificial no Desenvolvimento de Software: Impulsionando a Inovação e a Eficiência

Em 2025, a Inteligência Artificial (IA) se tornou uma ferramenta indispensável no desenvolvimento de software, transformando a maneira como os programadores trabalham e as soluções que eles criam. ...

-

Linguagens de Programação em Ascensão: Explorando as Tendências Emergentes

A indústria de tecnologia está em constante evolução, com novas linguagens de programação surgindo e ganhando popularidade a cada ano. Neste blog, vamos explorar algumas das linguagens de programaç...

-

Ecossistema de Aplicativos: 5 coisas essenciais para se ter dominio

Os ecossistemas de aplicativos estão se expandindo e se tornando mais complexos com o surgimento de aplicativos baseados em IA, esforços de modernização e novas iniciativas. Embora eu não ache que ...