-

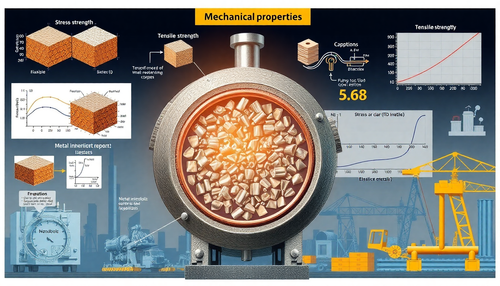

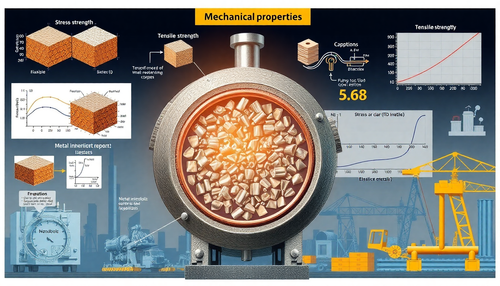

Propriedades Mecânicas dos Metais: Entendendo a Resistência e Durabilidade

Frequentemente, os materiais estão sujeitos a uma força externa quando são usados. Engenheiros mecânicos calculam essas forças, e cientistas de materiais determinam como os materiais se deformam ou...

-

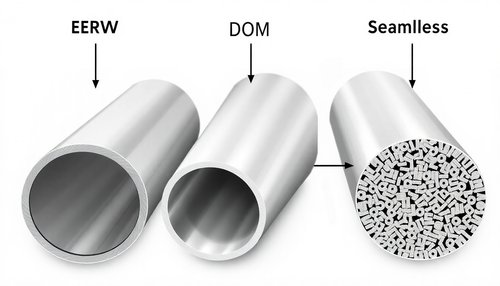

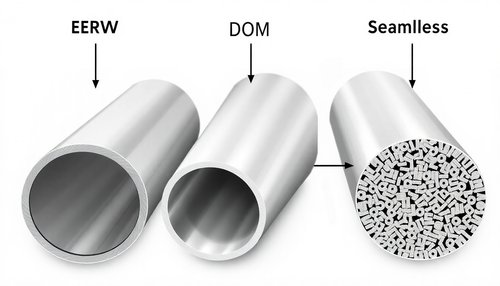

Entendendo os diferentes tipos de Tubos de Aço: ERW, DOM e Sem Costura

Este mês, examinamos as diferenças entre ERW, DOM e tubos sem costura. Tubos ERW (Electric Resistance Welded) ERW se refere a um processo de soldagem que envolve soldagem por pontos e por costura, ...

-

Como verificar a dureza do metal sem uma máquina Rockwell

Por muito tempo, pensei que a única maneira de verificar corretamente a dureza do metal era com uma máquina de teste Rockwell adequada. Felizmente, aprendi algumas outras técnicas simples e eficaze...

-

Curso com Planilhas Automáticas para Engenharia Civil

Planilhas Automáticas para Engenharia Civil: Cálculo e Dimensionamento Simplificados

Na engenharia civil, precisão e eficiência são vitais para o sucesso de qualquer projeto. No entanto, o process...

-

Curso de Power BI para Engenharia Civil

Power BI na Engenharia Civil: Da Introdução às Aplicações Avançadas

No cenário competitivo da engenharia civil e da construção, a capacidade de gerenciar e analisar dados se tornou uma habilidade ...

-

Cursos de Soldagem: Programa Completo para Iniciantes e Profissionais

Qualificação Profissional em Soldagem: Cursos Estratégicos para Atuar com Sucesso na Indústria

A soldagem é uma das habilidades mais críticas e requisitadas na indústria, especialmente em setores...

-

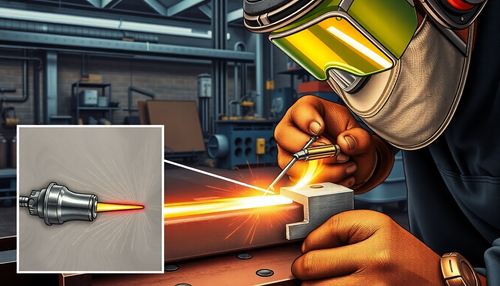

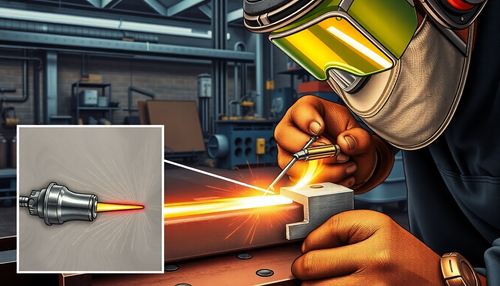

Como prolongar a Vida Útil do Bico de Contato na Solda MIG

A solda MIG (Metal Inert Gas) é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção devido à sua eficiência, versatilidade e qualidade dos resultados. No entanto, um componente crucial neste...

-

Como manter o Arco Elétrico Estável durante a Soldagem

A soldagem é uma técnica essencial em diversas indústrias, desde a construção civil até a fabricação de automóveis. No entanto, um dos desafios mais comuns enfrentados pelos soldadores é a manutenç...

-

Como Eliminar Respingos Excessivos na Soldagem MIG

A soldagem MIG (Metal Inert Gas) é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção, conhecida por sua eficiência e versatilidade. No entanto, um dos desafios comuns enfrentados pelos pro...

-

Como escolher o arame correto para solda MIG

A escolha do arame correto para solda MIG é fundamental para obter resultados de alta qualidade e eficiência no processo de soldagem. Cada tipo de arame possui características específicas que afeta...

-

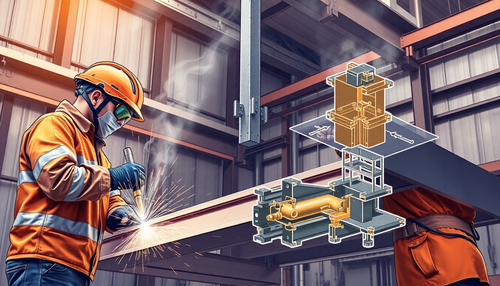

Soldagem de Tubulações em Campo: Preparação e Sequenciamento

A soldagem de tubulações em campo é um desafio único que requer habilidades especializadas e planejamento cuidadoso. Diferente da soldagem em ambiente controlado de oficina, a soldagem em campo enf...

-

Soldagem em Peças Pintadas: Evitando Problemas e Garantindo Segurança

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental em diversos setores industriais, desde a fabricação de automóveis até a construção civil. No entanto, quando se trata de soldar peças que já foram pintadas, é e...

-

Escovas de Aço na Soldagem: Preparação e Acabamento Perfeitos

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental em diversas indústrias, desde a construção civil até a fabricação de maquinário pesado. No entanto, para obter resultados de alta qualidade, é essencial prepara...

-

Entendendo o Processo de Brasagem: Quando e Como Utilizá-lo

A brasagem é uma técnica de união de metais que se diferencia da solda tradicional por fusão. Enquanto a solda envolve o derretimento e a mistura dos metais, a brasagem utiliza uma liga de metal de...

-

Importância da Limpeza Pós-Soldagem em Aço Inox e Alumínio

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental em diversos setores industriais, desde a construção civil até a fabricação de equipamentos. No entanto, após o processo de soldagem, é essencial realizar uma li...

-

Identificando e Corrigindo a Falta de Penetração na Solda

A integridade estrutural de uma junta soldada depende crucialmente da qualidade da penetração da solda. Quando a penetração é insuficiente, a resistência da união fica comprometida, podendo levar a...

-

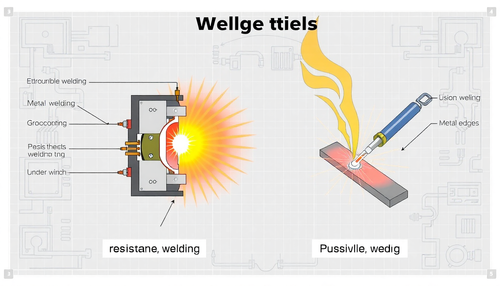

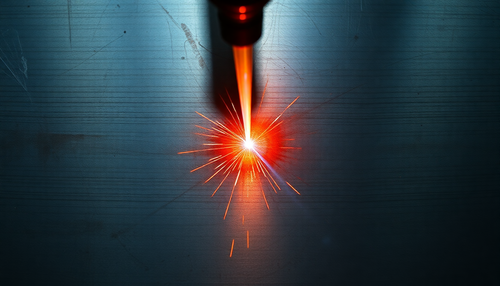

Processo de Soldagem por Resistência Elétrica: Entendendo os Detalhes Técnicos

A soldagem por resistência elétrica, também conhecida como solda por ponto ou spot weld, é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria, especialmente na fabricação de automóveis e estruturas metá...

-

Soldagem em Aço Inoxidável: Evitando os Erros Mais Comuns

A soldagem de aço inoxidável é uma tarefa delicada que requer atenção aos mínimos detalhes. Diferente da soldagem de aços carbono, o processo de união de peças em aço inoxidável envolve desafios es...

-

Importância do Controle da Velocidade de Avanço na Soldagem

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental em diversas indústrias, desde a construção civil até a fabricação de automóveis. No entanto, para obter resultados de alta qualidade, é essencial dominar divers...

-

Soldagem de Titânio: Superando Desafios e Impulsionando a Inovação

O titânio é um material fascinante, conhecido por sua resistência, leveza e biocompatibilidade. No entanto, a soldagem desse metal nobre apresenta desafios únicos que exigem técnicas especializadas...

-

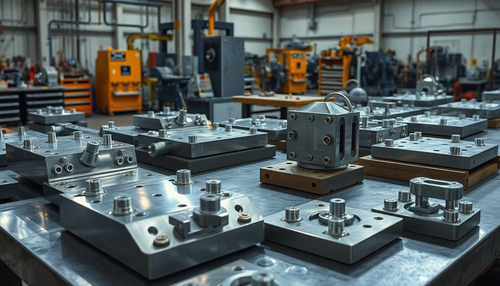

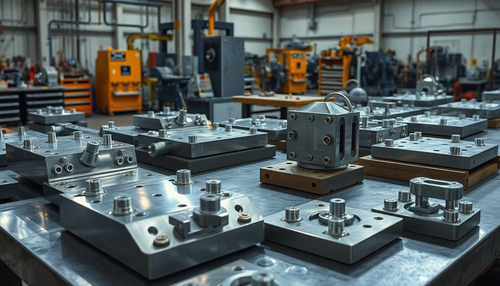

Como usar gabaritos e fixações para garantir soldagens precisas

A precisão é fundamental quando se trata de soldagem. Peças mal alinhadas ou deslocadas podem resultar em juntas defeituosas, reduzindo a integridade estrutural e a aparência final do trabalho. Fel...

-

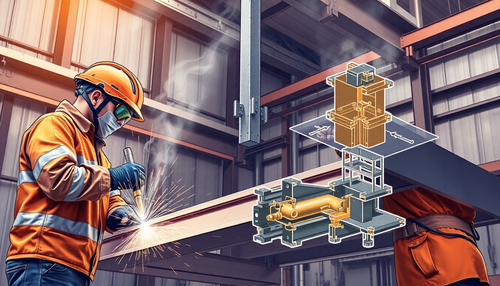

Técnicas Essenciais de Ponteamento para Montagem de Estruturas Metálicas

A montagem de estruturas metálicas é uma etapa crucial no processo de construção, exigindo técnicas precisas e cuidadosas para garantir a estabilidade e o alinhamento adequado das peças. Uma das té...

-

Poça de Fusão: Técnicas Essenciais para Soldagem TIG Perfeita

A soldagem TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) é uma técnica versátil e precisa, amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção. No entanto, manter a poça de fusão sob controle pode ser um desafio, especialme...

-

Soldagem a Plasma: Tecnologia para a Indústria e Construção

A soldagem a plasma, também conhecida como PAW (Plasma Arc Welding), é uma técnica de soldagem avançada que vem revolucionando a indústria e a construção. Essa tecnologia oferece uma solução eficie...

-

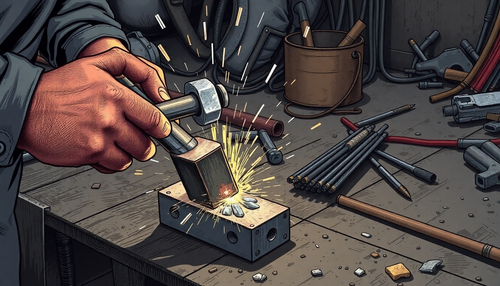

Importância do Martelo de Escória na Soldagem com Eletrodo Revestido

A soldagem com eletrodo revestido é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção civil, sendo essencial para a união de metais e a fabricação de estruturas robustas. No entanto, o pro...

-

Como fazer uma Solda Filetada com Qualidade Profissional

A solda filetada, também conhecida como solda em ângulo, é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e na construção civil para unir peças metálicas em ângulo. Essa técnica é essencial para a f...

-

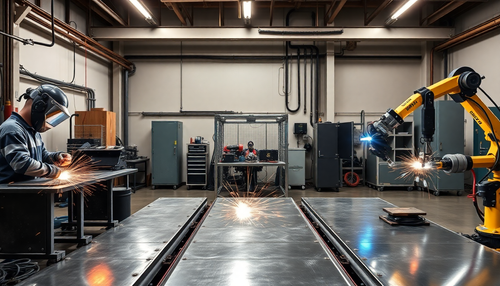

Entendendo os Tipos de Soldagem: Manual, Semiautomática e Automática

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental em diversos setores industriais, desde a fabricação de automóveis até a construção civil. No entanto, nem todas as técnicas de soldagem são iguais. Existem três...

-

Entendendo a Escorificação na Soldagem: Causas, Impactos e Soluções

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental em diversos setores industriais, desde a construção civil até a fabricação de máquinas e equipamentos. No entanto, durante o processo de soldagem, um fenômeno i...

-

Diferença entre solda TIG DC e TIG AC: quando usar cada uma

A solda TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção, conhecida por sua precisão, qualidade e versatilidade. No entanto, existem duas variantes principais d...

-

Soldagem em Aço Carbono Espesso: Desafios e Soluções

A soldagem de aço carbono espesso é um desafio constante para profissionais da indústria e construção. Essas peças exigem cuidados especiais durante o processo de soldagem, a fim de garantir a inte...

-

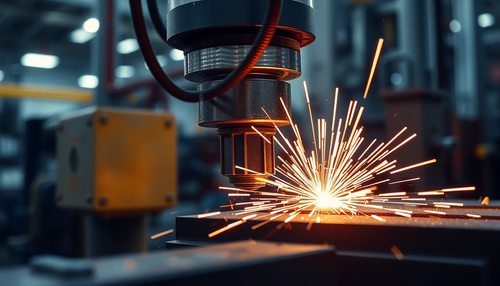

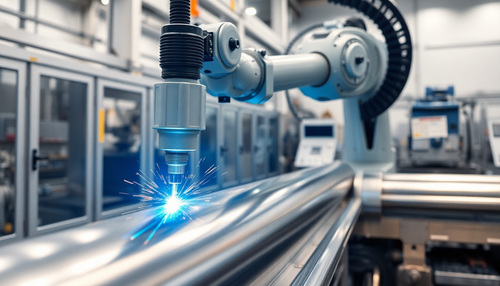

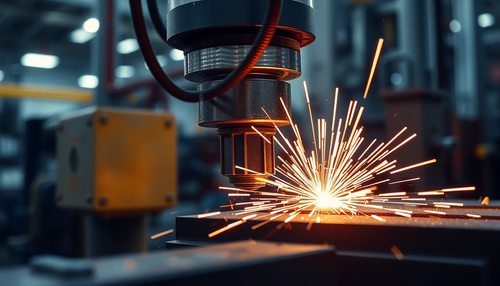

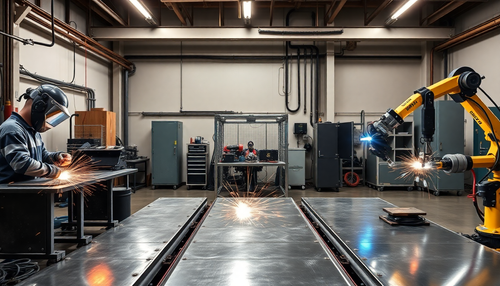

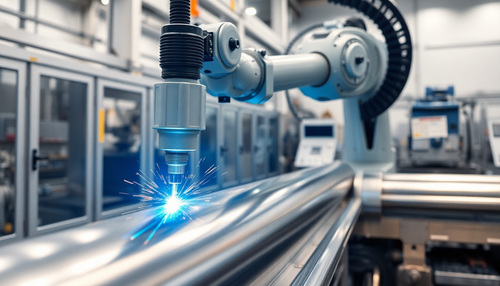

Como a Soldagem Robotizada Transforma a Indústria

A evolução tecnológica tem impulsionado transformações significativas em diversos setores industriais, e a soldagem robotizada é um exemplo claro dessa realidade. Essa técnica avançada vem se conso...

-

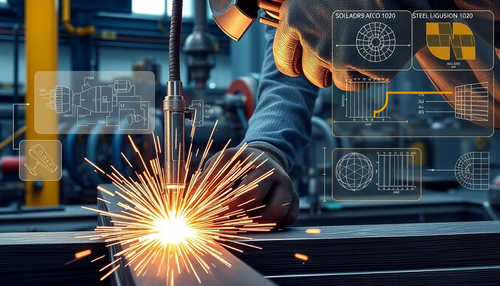

Soldar Aço 1020 corretamente: Evite trincas e Garanta Qualidade

O aço SAE AISI 1020 é um dos materiais mais utilizados na indústria e construção civil devido à sua versatilidade e custo-benefício. Esse aço carbono de baixa liga é amplamente empregado em estrutu...

-

Como Soldar Aço Inox com TIG Sem Contaminação: Um Guia Passo a Passo

A soldagem de aço inoxidável é uma tarefa delicada que requer atenção especial para evitar contaminação e obter um acabamento limpo e profissional. A técnica de soldagem TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) é ...

-

Como identificar e utilizar o Eletrodo 6013

O eletrodo 6013 é um dos tipos mais comuns e versáteis de eletrodos de soldagem utilizados na indústria e construção civil. Sua popularidade se deve às suas características únicas, que o tornam ide...

-

Como fazer uma Solda no Eletrodo Revestido

A solda com eletrodo revestido é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção civil devido à sua versatilidade e facilidade de aplicação. Neste artigo, vamos explorar detalhadamente o...

-

Garantia de Qualidade em Soldas: Os Principais Testes Não Destrutivos

A integridade e a qualidade das soldas são fundamentais em diversos setores industriais, desde a construção civil até a fabricação de equipamentos de alta tecnologia. Para assegurar que as juntas s...

-

Como ajustar Corretamente a Amperagem na Solda com Eletrodo Revestido

A solda com eletrodo revestido é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção, sendo essencial para a união de peças metálicas. Um dos fatores críticos neste processo é o ajuste preci...

-

Equipamentos de Proteção Individual (EPIs) obrigatórios para Soldadores

A segurança é um fator primordial no ambiente de trabalho, especialmente para profissionais que lidam com atividades de alto risco, como a soldagem. Os Equipamentos de Proteção Individual (EPIs) sã...

-

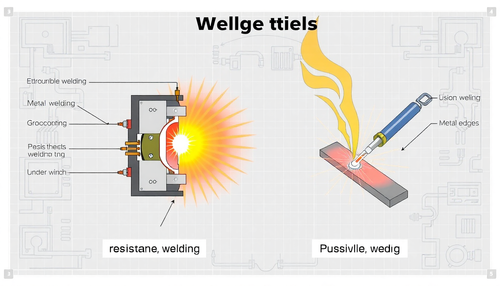

Diferença entre Solda por Resistência e Solda por Fusão: Aplicações Práticas

A escolha do processo de soldagem correto é crucial para garantir a integridade e a eficiência de diversas aplicações industriais, desde a fabricação de automóveis até a construção de aeronaves. Ne...

-

A Soldagem Orbital: Precisão e Eficiência

A soldagem orbital é uma técnica revolucionária que está transformando a maneira como as indústrias abordam a união de materiais. Essa abordagem automatizada e precisa tem se destacado em diversos ...

-

Como Regular sua Inversora MIG para Chapas Finas

A solda MIG (Metal Inert Gas) é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção, conhecida por sua versatilidade e eficiência. No entanto, quando se trata de trabalhar com chapas finas, ...

-

5 Erros Comuns na Soldagem com Alumínio

A soldagem de alumínio é uma técnica desafiadora que requer atenção aos detalhes e conhecimento especializado. Infelizmente, muitos profissionais cometem erros comuns que podem comprometer a qualid...

-

Como Prevenir Trincas a Quente e a Frio em Soldas

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental na indústria e construção, permitindo a união de peças metálicas de forma eficiente e resistente. No entanto, um desafio comum enfrentado pelos profissionais é ...

-

Soldagem com Arame Tubular: Praticidade, Penetração e Produtividade

A soldagem com arame tubular, também conhecida como FCAW (Flux-Cored Arc Welding), é um processo de soldagem amplamente utilizado na indústria e na construção civil. Essa técnica combina a praticid...

-

Diferença entre Solda Forte e Solda Branda

A escolha entre solda forte e solda branda é uma decisão crucial para muitos profissionais da indústria e construção. Cada uma dessas técnicas de união possui características únicas que as tornam a...

-

Soldagem por Fricção: Junção de Metais Leves

A indústria moderna enfrenta constantes desafios na busca por soluções de fabricação cada vez mais eficientes e sustentáveis. Nesse cenário, a técnica de soldagem por fricção (FSW - Friction Stir W...

-

Soldagem em Campo: Desafios e Soluções para Ambientes Adversos

A soldagem é uma técnica essencial em diversos setores industriais, desde a construção civil até a fabricação de equipamentos. No entanto, quando a soldagem precisa ser realizada fora do ambiente c...

-

Soldagem por Arco Submerso: Eficiência e Versatilidade na Indústria

A soldagem por arco submerso (SAW) é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria, conhecida por sua alta taxa de deposição e capacidade de soldar chapas grossas e estruturas pesadas. Este process...

-

A Solda de Tampão: Unindo Chapas com Eficiência e Resistência

A solda de tampão, também conhecida como solda de pino ou solda de ponto, é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e na construção civil para unir chapas sobrepostas de maneira rápida, efici...

-

Como obter um Acabamento Perfeito na Solda com Esmerilhamento Correto

Na indústria e construção, o acabamento superficial da solda é um fator crucial para a aparência final e a integridade estrutural de um projeto. Um acabamento mal feito pode comprometer a resistênc...

-

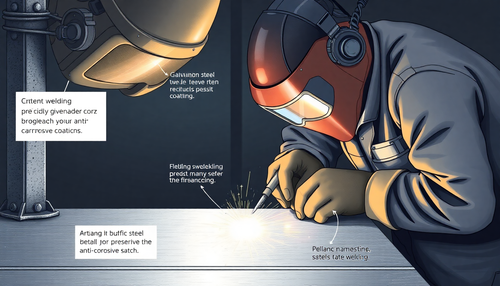

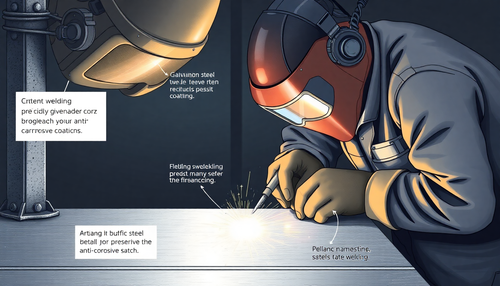

Como Soldar Aço Galvanizado sem comprometer a Proteção Anticorrosiva

A solda é uma técnica essencial na indústria e construção, permitindo a união de peças metálicas de forma segura e eficiente. No entanto, quando se trata de soldar aço galvanizado, existem desafios...

-

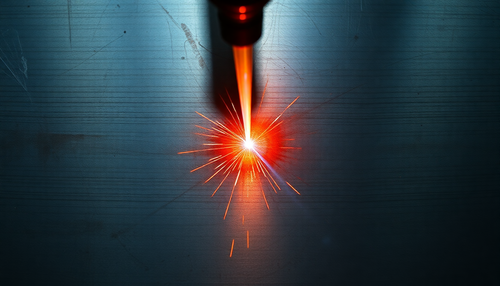

A Soldagem por Feixe de Elétrons: Técnica Avançada para Unir Metais com Precisão

A soldagem por feixe de elétrons (EBW) é uma técnica avançada de união de metais que utiliza um feixe de elétrons acelerados em uma câmara de vácuo para fundir e soldar materiais com precisão milim...

-

Soldagem em Tubulações: Desafios e Técnicas Essenciais

A soldagem em tubulações é uma tarefa crítica na indústria e construção, exigindo habilidades especializadas e técnicas avançadas. Neste artigo, exploraremos os desafios técnicos envolvidos nesse t...

-

Como o ângulo da tocha afeta a solda MIG

A solda MIG (Soldagem por Gás de Metal) é uma técnica amplamente utilizada na indústria e construção, conhecida por sua eficiência e versatilidade. Um dos fatores-chave que influenciam diretamente ...

-

Soldagem em Alumínio: Principais cuidados e Técnicas Recomendadas

O alumínio é um material amplamente utilizado na indústria e na construção civil devido às suas propriedades únicas, como leveza, resistência à corrosão e alta condutividade elétrica e térmica. No ...

-

Como lidar com Rachaduras na Solda ao Resfriar o Cordão

A soldagem é uma técnica fundamental na indústria e construção, permitindo a união de peças metálicas de forma eficiente e resistente. No entanto, um desafio comum que os profissionais enfrentam é ...